Gauge fixing

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

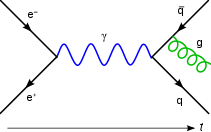

Feynman diagram

|

| History |

Although the unphysical axes in the space of detailed configurations are a fundamental property of the physical model, there is no special set of directions "perpendicular" to them. Hence there is an enormous amount of freedom involved in taking a "cross section" representing each physical configuration by a particular detailed configuration (or even a weighted distribution of them). Judicious gauge fixing can simplify calculations immensely, but becomes progressively harder as the physical model becomes more realistic; its application to quantum field theory is fraught with complications related to renormalization, especially when the computation is continued to higher orders. Historically, the search for logically consistent and computationally tractable gauge fixing procedures, and efforts to demonstrate their equivalence in the face of a bewildering variety of technical difficulties, has been a major driver of mathematical physics from the late nineteenth century to the present.[citation needed]

Contents

[hide]Gauge freedom[edit]

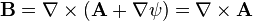

The archetypical gauge theory is the Heaviside–Gibbs formulation of continuum electrodynamics in terms of an electromagnetic four-potential, which is presented here in space/time asymmetric Heaviside notation. The electric field E and magnetic field B of Maxwell's equations contain only "physical" degrees of freedom, in the sense that every mathematical degree of freedom in an electromagnetic field configuration has a separately measurable effect on the motions of test charges in the vicinity. These "field strength" variables can be expressed in terms of the electric scalar potential and the magnetic vector potential A through the relations:

and the magnetic vector potential A through the relations: (1)

(1)

.

.

.

.

(2)

(2)

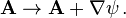

A particular choice of the scalar and vector potentials is a gauge (more precisely, gauge potential) and a scalar function ψ used to change the gauge is called a gauge function. The existence of arbitrary numbers of gauge functions ψ(r, t) corresponds to the U(1) gauge freedom of this theory. Gauge fixing can be done in many ways, some of which we exhibit below.

Although classical electromagnetism is now often spoken of as a gauge theory, it was not originally conceived in these terms. The motion of a classical point charge is affected only by the electric and magnetic field strengths at that point, and the potentials can be treated as a mere mathematical device for simplifying some proofs and calculations. Not until the advent of quantum field theory could it be said that the potentials themselves are part of the physical configuration of a system. The earliest consequence to be accurately predicted and experimentally verified was the Aharonov–Bohm effect, which has no classical counterpart. Nevertheless, gauge freedom is still true in these theories. For example, the Aharonov–Bohm effect depends on a line integral of A around a closed loop, and this integral is not changed by

An illustration[edit]

Quantum superposition

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

|

An example of a physically observable manifestation of superposition is interference peaks from an electron wave in a double-slit experiment.

Another example is a quantum logical qubit state, as used in quantum information processing, which is a linear superposition of the "basis states"

and

and  . Here

. Here  is the Dirac notation for the quantum state that will always give the result 0 when converted to classical logic by a measurement. Likewise

is the Dirac notation for the quantum state that will always give the result 0 when converted to classical logic by a measurement. Likewise  is the state that will always convert to 1.

is the state that will always convert to 1.Contents

[hide]Theory[edit]

| This section does not cite any sources. (November 2015) |

Examples[edit]

For an equation describing a physical phenomenon, the superposition principle states that a combination of solutions to a linear equation is also a solution of it. When this is true the equation is said to obey the superposition principle. Thus if state vectors f1, f2 and f3 each solve the linear equation on ψ, then ψ = c1 f1 + c2 f2 + c3 f3 would also be a solution, in which each c is a coefficient. The Schrödinger equation is linear, so quantum mechanics follows this.For example, consider an electron with two possible configurations, up and down. This describes the physical system of a qubit.

. The probability for down is

. The probability for down is  . Note that

. Note that  .

.In the description, only the relative size of the different components matter, and their angle to each other on the complex plane. This is usually stated by declaring that two states which are a multiple of one another are the same as far as the description of the situation is concerned. Either of these describe the same state for any nonzero

turns into a mixture of A′ and B′ with the same coefficients as A and B.

turns into a mixture of A′ and B′ with the same coefficients as A and B.[PDF]Quantization of Gauge Theories

eduardo.physics.illinois.edu/...

Unlike systems which only have global symmetries, not all the classical configurations of vector potentials represent physically distinct states. It could be argued ...

University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

Loading...

Gauge fixing - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gauge_fixing

Any two detailed configurations in the same equivalence class are related by a gauge ... A particular choice of the scalar and vector potentials is a gauge (more .... not depend on the gauge function is said to be gauge invariant: all physical ... states, which are not observed in experiments at classical distance scales, one ...

Wikipedia

Loading...

Quantum superposition - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_superposition

It states that much like waves in classical physics, any two (or more) quantum ... state can be represented as a sum of two or more other distinct states. ... For an equation describing a physical phenomenon, the superposition principle states that a ... Thus if state vectors f1, f2 and f3 each solve the linear equation on ψ, then ψ ...

Wikipedia

Loading...

Gauge theory - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gauge_theory

Its case is somewhat unique in that the gauge field is a tensor, the Lanczos tensor. ... 3.1 Classical electromagnetism; 3.2 An example: Scalar O(n) gauge theory .... orbit of mathematical configurations that represent a given physical situation to a ... to electromagnetism, we have a second potential, the vector potential A, with.

Wikipedia

Loading...

Euclidean Quantum Gravity - Page 131 - Google Books Result

https://books.google.com/books?isbn=9810205163

G. W. Gibbons, Stephen W. Hawking - 1993 - Science

This manipulation is not needed to construct Euclidean functional integrals ... the classical Euclidean actions of these theories are manifestly positive. ... given in a form in which not all field configurations are physically distinct. ... In electromagnetism, the physical fields are the transverse components of the vector potential Af; ...

No comments:

Post a Comment