We now need to meet the boundary condition on the first derivative at

The Delta Function Model of a Molecule *

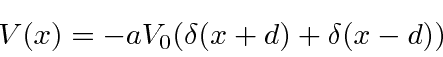

The use of two delta functions allows us to see, to some extent, how atoms bind into molecules. Our potential is

with attractive delta functions at

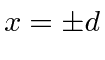

. This is a parity symmetric potential, so we can assume that our solutions will be parity eigenstates.

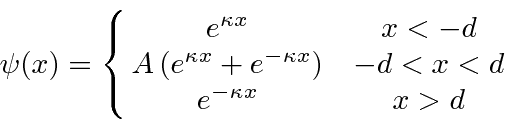

. This is a parity symmetric potential, so we can assume that our solutions will be parity eigenstates. For even parity, our solution in the three regions is

Since the solution is designed to be symmetric about

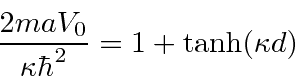

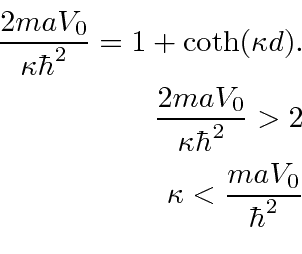

A little calculation gives

This is a transcendental equation, but we can limit the energy.

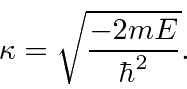

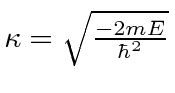

Since

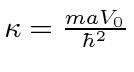

for the single delta function, this

for the single delta function, this  is larger than the one for the single delta function. This means that

is larger than the one for the single delta function. This means that

Basically, the electron doesn't have to be a localized with two atoms as it does with just one. This allows the kinetic energy to be lower.

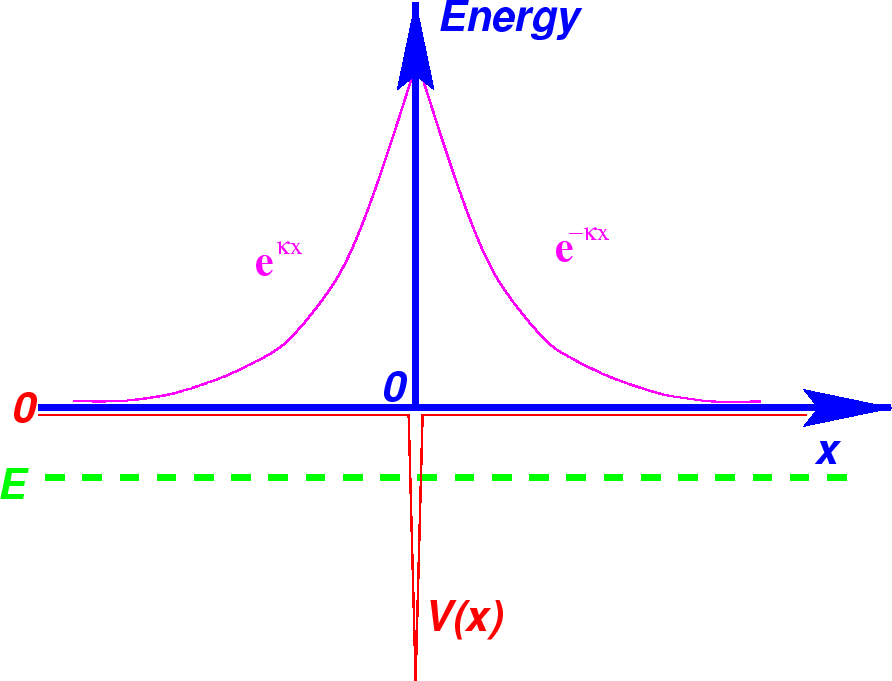

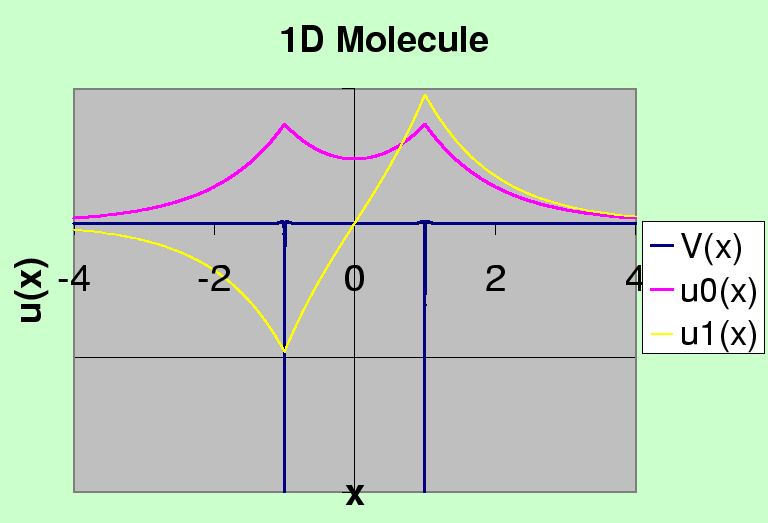

The figure below shows the two solutions plotted on the same graph as the potential.

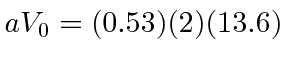

Two Hydrogen atoms bind together to form a molecule with a separation of 0.74 Angstroms, just larger than the Bohr radius of 0.53 Angstroms. The binding energy (for the two electrons) is about 4.5 eV. If we approximate the Coulomb potential by with a delta function, setting

eV Angstroms, our very naive calculation would give 1.48 eV for one electron, which is at least the right order of magnitude. The odd parity solution has an energy that satisfies the equation

eV Angstroms, our very naive calculation would give 1.48 eV for one electron, which is at least the right order of magnitude. The odd parity solution has an energy that satisfies the equation

This energy is larger than for one delta function. This state would be called anti-bonding.

No comments:

Post a Comment